Visualization

Last updated on 2025-12-12 | Edit this page

Estimated time: 130 minutes

Overview

Questions

- What elements make a compelling visualization that authentically reports scientific results ready for scientific presentation and publication?

- What tools and techniques are available to save time on creating presentation and publication-ready figures?

Objectives

- Design a figure that tells a compelling story.

- Use Matplotlib features to customize the appearance of figures.

- Generate a figure with multiple subplots.

In the previous episode, we selected photometry data from Pan-STARRS and used it to identify stars we think are likely to be in GD-1.

In this episode, we will take the results from previous episodes and use them to make a figure that tells a compelling scientific story.

Outline

Starting with the figure from the previous episode, we will add annotations to present the results more clearly.

Then we will learn several ways to customize figures to make them more appealing and effective.

Finally, we will learn how to make a figure with multiple panels.

Starting from this episode

If you are starting a new notebook for this episode, expand this section for information you will need to get started.

In the previous episode, we selected stars in GD-1 based on proper motion and downloaded the spatial, proper motion, and photometry information by joining the Gaia and PanSTARRs datasets. We will use that data for this episode. Whether you are working from a new notebook or coming back from a checkpoint, reloading the data will save you from having to run the query again.

If you are starting this episode here or starting this episode in a new notebook, you will need to run the following lines of code.

This imports previously imported functions:

PYTHON

import pandas as pd

import numpy as np

from matplotlib import pyplot as plt

from matplotlib.patches import Polygon

from episode_functions import *The following code loads in the data (instructions for downloading

data can be found in the setup instructions).

You may need to add a the path to the filename variable below

(e.g. filename = 'student_download/backup-data/gd1_data.hdf')

PYTHON

filename = 'gd1_data.hdf'

winner_df = pd.read_hdf(filename, 'winner_df')

centerline_df = pd.read_hdf(filename, 'centerline_df')

candidate_df = pd.read_hdf(filename, 'candidate_df')

loop_df = pd.read_hdf(filename, 'loop_df')This defines previously defined quantities:

Making Figures That Tell a Story

The figures we have made so far have been “quick and dirty”. Mostly

we have used Matplotlib’s default style, although we have adjusted a few

parameters, like markersize and alpha, to

improve legibility.

Now that the analysis is done, it is time to think more about:

Making professional-looking figures that are ready for publication.

Making figures that communicate a scientific result clearly and compellingly.

Not necessarily in that order.

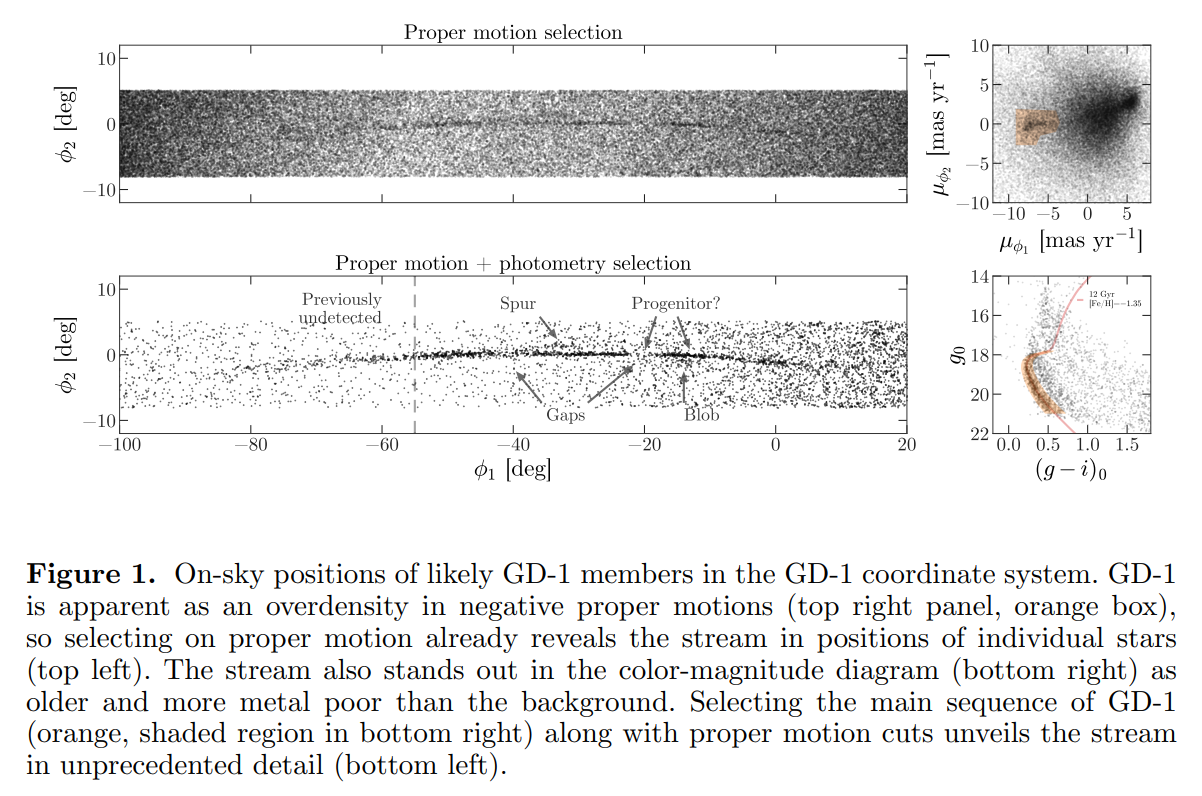

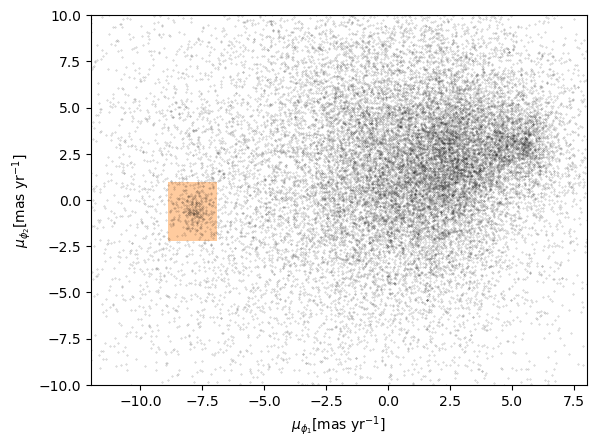

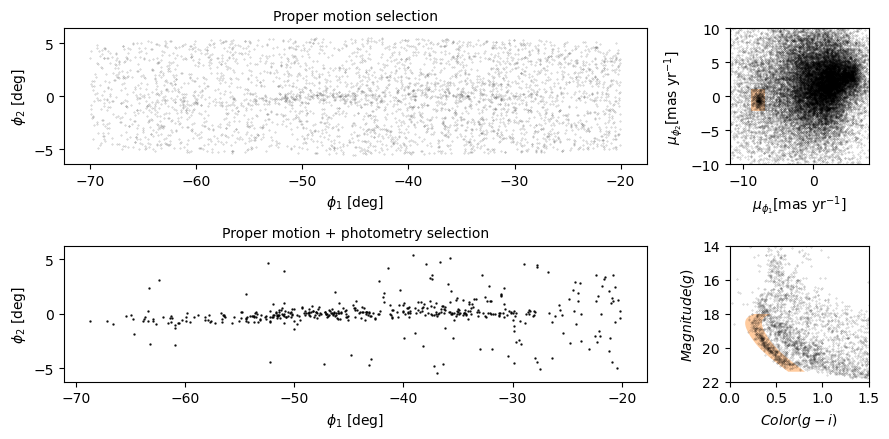

We will start by reviewing Figure 1 from the original paper. We have seen the individual panels, but now we will look at the whole figure, along with the caption:

Exercise (10 minutes)

Think about the following questions:

What is the primary scientific result of this work?

What story is this figure telling?

In the design of this figure, can you identify 1 or 2 choices the authors made that you think are effective? Think about big-picture elements, like the number of panels and how they are arranged, as well as details like the choice of typeface.

Can you identify 1 or 2 elements that could be improved, or that you might have done differently?

No figure is perfect, and everyone can be a critic. Here are some topics that could come up in this discussion:

The primary result is that adding physical selection criteria makes it possible to separate likely candidates from the background more effectively than in previous work, which makes it possible to see the structure of GD-1 in “unprecedented detail,” allowing the authors to detect that the stream is larger than previously observed.

The figure documents the selection process as a sequence of reproducible steps, containing enough information for a skeptical reader to understand the authors’ choices. Reading right-to-left, top-to-bottom, we see selection based on proper motion, the results of the first selection, selection based on stellar surface properties (color and magnitude), and the results of the second selection. So this figure documents the methodology, presents the primary result, and serves as reference for other parts of the paper (and presumably, talk, if this figure is reused for colloquia).

The figure is mostly black and white, with minimal use of color, and mostly uses large fonts. It will likely work well in print and only needs a few adjustments to be accessible to low vision readers and none to accommodate those with poor color vision. The annotations in the bottom left panel guide the reader to the results discussed in the text.

The panels that can have the same units, dimensions, and their axes are aligned, do.

The on-sky positions likely do not need so much white space.

Axes ticks for the on-sky position figures are not necessary since this is not in an intuitive coordinate system or a finder chart. Instead, we would suggest size bar annotations for each dimension to give the reader the needed scale.

The text annotations could be darker for more contrast and appear only over white background to increase accessibility

The legend in the bottom right panel has a font too small for low-vision readers. At the very least, those details (and the isochrone line) could be called out in the caption.

Plotting GD-1 with Annotations

The lower left panel in the paper uses three other features to present the results more clearly and compellingly:

A vertical dashed line to distinguish the previously undetected region of GD-1,

A label that identifies the new region, and

Several annotations that combine text and arrows to identify features of GD-1.

Exercise (20 minutes)

Plot the selected stars in winner_df using the

plot_cmd_selection function and then choose any or all of

these features and add them to the figure:

To draw vertical lines, see

plt.vlinesandplt.axvline.To add text, see

plt.text.To add an annotation with text and an arrow, see

plt.annotate.

Here is some additional information about text and arrows.

PYTHON

fig = plt.figure(figsize=(10,2.5))

plot_cmd_selection(winner_df)

plt.axvline(-55, ls='--', color='gray',

alpha=0.4, dashes=(6,4), lw=2)

plt.text(-60, 5.5, 'Previously\nundetected',

fontsize='small', ha='right', va='top')

arrowprops=dict(color='gray', shrink=0.05, width=1.5,

headwidth=6, headlength=8, alpha=0.4)

plt.annotate('Spur', xy=(-33, 2), xytext=(-35, 5.5),

arrowprops=arrowprops,

fontsize='small')

plt.annotate('Gap', xy=(-22, -1), xytext=(-25, -5.5),

arrowprops=arrowprops,

fontsize='small');Customization

Matplotlib provides a default style that determines things like the colors of lines, the placement of labels and ticks on the axes, and many other properties.

There are several ways to override these defaults and customize your figures:

To customize only the current figure, you can call functions like

tick_params, which we will demonstrate below.To customize all figures in a notebook, you can use

rcParams.To override more than a few defaults at the same time, you can use a style sheet.

As a simple example, notice that Matplotlib puts ticks on the outside of the figures by default, and only on the left and bottom sides of the axes.

Note on Accessibility

Customization offers a high degree of personalization for creating scientific visualizations. It is important to also create accessible visualizations for a broad audience that may include low-vision or color-blind individuals. The AAS Journals provide a Graphics Guide for authors with tips and external links that can help you produce more accessible graphics: https://journals.aas.org/graphics-guide/

So far, everything we have wanted to do we could call directly from

the pyplot module with plt.. As you do more and more

customization you may need to run some methods on plotting objects

themselves. To use the method that changes the direction of the ticks we

need an axes object. So far, Matplotlib has implicitly

created our axes object when we called

plt.plot. To explicitly create an axes object

we can first create our figure object and then add an

axes object to it.

subplot and

axes

Confusingly, in Matplotlib the objects subplot and

axes are often used interchangeably. This is because a

subplot is an axes object with additional

methods and attributes.

You can use the add_subplot

method to add more than one axes object to a figure. For

this reason you have to specify the total number of columns, total

number of rows, and which plot number you are creating

(fig.add_subplot(ncols, nrows, pltnum)). The plot number

starts in the upper left corner and goes left to right and then top to

bottom. In the example above we have one column, one row, and we’re

plotting into the first plot space.

Now we are ready to change the direction of the ticks to the inside of the axes using our new axes object.

PYTHON

fig = plt.figure(figsize=(10,2.5))

ax = fig.add_subplot(1,1,1)

ax.tick_params(direction='in')Exercise (5 minutes)

Read the documentation of tick_params

and use it to put ticks on the top and right sides of the axes.

rcParams

If you want to make a customization that applies to all figures in a

notebook, you can use rcParams. When you import Matplotlib,

a dictionary is created with default values for everything you can

change about your plot. This is what you are overriding with

tick_params above.

Here is an example that reads the current font size from

rcParams:

OUTPUT

10.0And sets it to a new value:

Exercise (5 minutes)

Plot the previous figure again, and see what font sizes have changed.

Look up any other element of rcParams, change its value,

and check the effect on the figure.

PYTHON

fig = plt.figure(figsize=(10,2.5))

ax = fig.add_subplot(1,1,1)

ax.tick_params(top=True, right=True)

# Looking up the 'axes.edgecolor' rcParams value

print(plt.rcParams['axes.edgecolor'])

plt.rcParams['axes.edgecolor'] = 'red'

fig = plt.figure(figsize=(10,2.5))

ax = fig.add_subplot(1,1,1)

ax.tick_params(top=True, right=True)

# changing the rcParams value back to its original value

plt.rcParams['axes.edgecolor'] = 'black'When you import Matplotlib, plt.rcParams is populated

from a matplotlibrc file. If you want to permanently change a setting

for every plot you make, you can set that in your matplotlibrc file. To

find out where your matplotlibrc file lives type:

If the file doesn’t exist, you can download a sample matplotlibrc file to modify.

Style sheets

It is possible that you would like multiple sets of defaults, for

example, one default for plots for scientific papers and another for

talks or posters. Because the matplotlibrc file is read

when you import Matplotlib, it is not easy to switch from one set of

options to another.

The solution to this problem is style sheets, which you can read about here.

Matplotlib provides a set of predefined style sheets, or you can make your own. The style sheets reference shows a gallery of plots generated by common style sheets.

You can display a list of style sheets installed on your system.

OUTPUT

['Solarize_Light2',

'_classic_test_patch',

'bmh',

'classic',

'dark_background',

'fast',

'fivethirtyeight',

'ggplot',

'grayscale',

'seaborn',

'seaborn-bright',

[Output truncated]Note that seaborn-paper, seaborn-talk and

seaborn-poster are particularly intended to prepare

versions of a figure with text sizes and other features that work well

in papers, talks, and posters.

To use any of these style sheets, run plt.style.use like

this:

The style sheet you choose will affect the appearance of all figures

you plot after calling use, unless you override any of the

options or call use again.

Exercise (5 minutes)

Choose one of the styles on the list and select it by calling

use. Then go back and plot one of the previous figures to

see what changes in the figure’s appearance.

If you cannot find a style sheet that is exactly what you want, you

can make your own. This repository includes a style sheet called

az-paper-twocol.mplstyle, with customizations chosen by

Azalee Bostroem for publication in astronomy journals.

You can use it like this:

PYTHON

plt.style.use('./az-paper-twocol.mplstyle')

plot_cmd(candidate_df)

plt.plot(loop_df['color_loop'], loop_df['mag_loop'], g, label='GD1 Isochrone loop')

plt.legend();The prefix ./ tells Matplotlib to look for the file in

the current directory.

As an alternative, you can install a style sheet for your own use by

putting it into a directory named stylelib/ in your

configuration directory.

To find out where the Matplotlib configuration directory is, you can run

the following command:

Multiple panels

So far we have been working with one figure at a time, but the figure

we are replicating contains multiple panels. We will create each of

these panels as a different subplot. Matplotlib has multiple functions

for making figures with multiple panels. We have already used add_subplot

- however, this creates equal sized panels. For this reason, we will use

subplot2grid

which allows us to control the relative sizes of the panels.

Since we have already written functions that generate each panel of this figure, we can now create the full multi-panel figure by creating each subplot and then run our plotting function.

Like add_subplot,

subplot2grid

requires us to specify the total number of columns and rows in the grid

(this time as a tuple called shape), and the location of

the subplot (loc) - a tuple identifying the location in the

grid we are about to fill.

In this example, shape is (2, 2) to create

two rows and two columns.

For the first panel, loc is (0, 0), which

indicates row 0 and column 0, which is the upper-left panel.

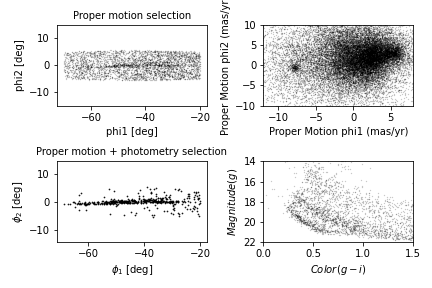

Here is how we use this function to draw the four panels.

PYTHON

plt.style.use('default')

fig = plt.figure()

shape = (2, 2)

ax1 = plt.subplot2grid(shape, (0, 0))

plot_pm_selection(candidate_df)

ax2 = plt.subplot2grid(shape, (0, 1))

plot_proper_motion(centerline_df)

ax3 = plt.subplot2grid(shape, (1, 0))

plot_cmd_selection(winner_df)

ax4 = plt.subplot2grid(shape, (1, 1))

plot_cmd(candidate_df)

plt.tight_layout()OUTPUT

<Figure size 640x480 with 4 Axes>

We use plt.tight_layout

at the end, which adjusts the sizes of the panels to make sure the

titles and axis labels don’t overlap. Notice how convenient it is that

we have written functions to plot each panel. This code is concise and

readable: we can tell what is being plotted in each panel thanks to our

explicit function names and we know what function to investigate if we

want to see the mechanics of exactly how the plotting is done.

Exercise (5 minutes)

What happens if you leave out tight_layout?

Without tight_layout the space between the panels is too

small. In this situation, the titles from the lower plots overlap with

the x-axis labels from the upper panels and the axis labels from the

right-hand panels overlap with the plots in the left-hand panels.

Adjusting proportions

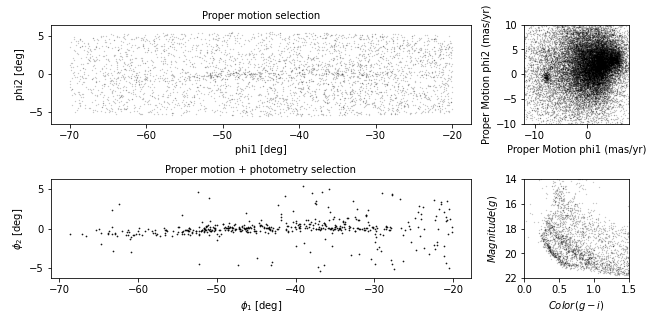

In the previous figure, the panels are all the same size. To get a better view of GD-1, we would like to stretch the panels on the left and compress the ones on the right.

To do that, we will use the colspan argument to make a

panel that spans multiple columns in the grid. To do this we will need

more columns so we will change the shape from (2,2) to

(2,4).

The panels on the left span three columns, so they are three times wider than the panels on the right.

At the same time, we use figsize to adjust the aspect

ratio of the whole figure.

PYTHON

plt.figure(figsize=(9, 4.5))

shape = (2, 4)

ax1 = plt.subplot2grid(shape, (0, 0), colspan=3)

plot_pm_selection(candidate_df)

ax2 = plt.subplot2grid(shape, (0, 3))

plot_proper_motion(centerline_df)

ax3 = plt.subplot2grid(shape, (1, 0), colspan=3)

plot_cmd_selection(winner_df)

ax4 = plt.subplot2grid(shape, (1, 3))

plot_cmd(candidate_df)

plt.tight_layout()OUTPUT

<Figure size 900x450 with 4 Axes>

This is looking more and more like the figure in the paper.

Exercise (5 minutes)

In this example, the ratio of the widths of the panels is 3:1. How would you adjust it if you wanted the ratio to be 3:2?

PYTHON

plt.figure(figsize=(9, 4.5))

shape = (2, 5) # CHANGED

ax1 = plt.subplot2grid(shape, (0, 0), colspan=3)

plot_pm_selection(candidate_df)

ax2 = plt.subplot2grid(shape, (0, 3), colspan=2) # CHANGED

plot_proper_motion(centerline_df)

ax3 = plt.subplot2grid(shape, (1, 0), colspan=3)

plot_cmd_selection(winner_df)

ax4 = plt.subplot2grid(shape, (1, 3), colspan=2) # CHANGED

plot_cmd(candidate_df)

plt.tight_layout()Adding the shaded regions

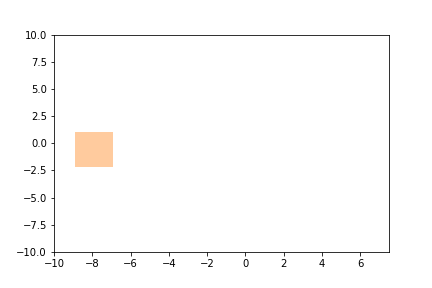

The one thing our figure is missing is the shaded regions showing the stars selected by proper motion and around the isochrone in the color magnitude diagram.

In episode 4 we defined a rectangle in proper motion space around the

stars in GD-1. We stored the x-values of the vertices of this rectangle

in pm1_rect and the y-values as pm2_rect.

To plot this rectangle, we will use the Matplotlib

Polygon object which we used in episode 7 to check which

points were inside the polygon. However, this time we will be plotting

the Polygon.

To create a Polygon, we have to put the coordinates of

the rectangle in an array with x values in the first column

and y values in the second column.

OUTPUT

array([[-8.9, -2.2],

[-8.9, 1. ],

[-6.9, 1. ],

[-6.9, -2.2]])We will now create the Polygon, specifying its display

properties which will be used when it is plotted. We will specify

closed=True to make sure the shape is closed,

facecolor='orange to color the inside of the

Polygon orange, and alpha=0.4 to make the

Polygon semi-transparent.

Then to plot the Polygon we call the

add_patch method. add_patch like

tick_params must be called on an axes or

subplot object, so we will create a subplot

and then add the Patch to the subplot.

PYTHON

fig = plt.figure()

ax = fig.add_subplot(1,1,1)

poly = Polygon(vertices, closed=True,

facecolor='orange', alpha=0.4)

ax.add_patch(poly)

ax.set_xlim(-10, 7.5)

ax.set_ylim(-10, 10)OUTPUT

<Figure size 900x450 with 4 Axes>

We can now call our plot_proper_motion function to plot the proper

motion for each star, and then add a shaded Polygon to show

the region we selected.

PYTHON

fig = plt.figure()

ax = fig.add_subplot(1,1,1)

plot_proper_motion(centerline_df)

poly = Polygon(vertices, closed=True,

facecolor='C1', alpha=0.4)

ax.add_patch(poly)OUTPUT

<Figure size 900x450 with 4 Axes>

Exercise (5 minutes)

Add a few lines to be run after the plot_cmd function to

show the polygon we selected as a shaded area.

Hint: pass loop_df as an argument to

Polygon as we did in episode 7 and then plot it using

add_patch.

Exercise (5 minutes)

Add the Polygon patches you just created to the right

panels of the four panel figure.

PYTHON

fig = plt.figure(figsize=(9, 4.5))

shape = (2, 4)

ax1 = plt.subplot2grid(shape, (0, 0), colspan=3)

plot_pm_selection(candidate_df)

ax2 = plt.subplot2grid(shape, (0, 3))

plot_proper_motion(centerline_df)

poly = Polygon(vertices, closed=True,

facecolor='orange', alpha=0.4)

ax2.add_patch(poly)

ax3 = plt.subplot2grid(shape, (1, 0), colspan=3)

plot_cmd_selection(winner_df)

ax4 = plt.subplot2grid(shape, (1, 3))

plot_cmd(candidate_df)

poly_cmd = Polygon(loop_df, closed=True,

facecolor='orange', alpha=0.4)

ax4.add_patch(poly_cmd)

plt.tight_layout()OUTPUT

<Figure size 900x450 with 4 Axes>

Summary

In this episode, we reverse-engineered the figure we have been replicating, identifying elements that seem effective and others that could be improved.

We explored features Matplotlib provides for adding annotations to figures – including text, lines, arrows, and polygons – and several ways to customize the appearance of figures. And we learned how to create figures that contain multiple panels.

- Effective figures focus on telling a single story clearly and authentically. The major decisions needed in creating an effective summary figure like this one can be done away from a computer and built up from low fidelity (hand drawn) to high (tweaking rcParams, etc.).

- Consider using annotations to guide the reader’s attention to the most important elements of a figure, while keeping in mind accessibility issues that such detail may introduce.

- The default Matplotlib style generates good quality figures, but there are several ways you can override the defaults.

- If you find yourself making the same customizations on several projects, you might want to create your own style sheet.