R Basics continued - factors and data frames

Last updated on 2026-02-08 | Edit this page

Overview

Questions

- How do I get started with tabular data (e.g. spreadsheets) in R?

- What are some best practices for reading data into R?

- How do I save tabular data generated in R?

Objectives

- Explain the basic principle of tidy datasets

- Be able to load a tabular dataset using base R functions

- Be able to determine the structure of a data frame including its dimensions and the datatypes of variables

- Be able to subset/retrieve values from a data frame

- Understand how R may coerce data into different modes

- Be able to change the mode of an object

- Understand that R uses factors to store and manipulate categorical data

- Be able to manipulate a factor, including subsetting and reordering

- Be able to apply an arithmetic function to a data frame

- Be able to coerce the class of an object (including variables in a data frame)

- Be able to import data from Excel

- Be able to save a data frame as a delimited file

Working with spreadsheets (tabular data)

A substantial amount of the data we work with in genomics will be tabular data, this is data arranged in rows and columns - also known as spreadsheets. We could write a whole lesson on how to work with spreadsheets effectively (actually we did). For our purposes, we want to remind you of a few principles before we work with our first set of example data:

1) Keep raw data separate from analyzed data

This is principle number one because if you can’t tell which files are the original raw data, you risk making some serious mistakes (e.g. drawing conclusion from data which have been manipulated in some unknown way).

2) Keep spreadsheet data Tidy

The simplest principle of Tidy data is that we have one row in our spreadsheet for each observation or sample, and one column for every variable that we measure or report on. As simple as this sounds, it’s very easily violated. Most data scientists agree that significant amounts of their time is spent tidying data for analysis. Read more about data organization in our lesson and in this paper.

3) Trust but verify

Finally, while you don’t need to be paranoid about data, you should have a plan for how you will prepare it for analysis. This a focus of this lesson. You probably already have a lot of intuition, expectations, assumptions about your data - the range of values you expect, how many values should have been recorded, etc. Of course, as the data get larger our human ability to keep track will start to fail (and yes, it can fail for small data sets too). R will help you to examine your data so that you can have greater confidence in your analysis, and its reproducibility.

Tip: Keep your raw data separate

When you work with data in R, you are not changing the original file

you loaded that data from. This is different than (for example) working

with a spreadsheet program where changing the value of the cell leaves

you one “save”-click away from overwriting the original file. You have

to purposely use a writing function (e.g. write.csv()) to

save data loaded into R. In that case, be sure to save the manipulated

data into a new file. More on this later in the lesson.

Importing tabular data into R

There are several ways to import data into R. For our purpose here,

we will focus on using the tools every R installation comes with (so

called “base” R) to import a comma-delimited file containing the results

of our variant calling workflow. We will need to load the sheet using a

function called read.csv().

Exercise: Review the arguments of the

read.csv() function

Before using the read.csv() function, use R’s

help feature to answer the following questions.

Hint: Entering ‘?’ before the function name and then running that line will bring up the help documentation. Also, when reading this particular help be careful to pay attention to the ‘read.csv’ expression under the ‘Usage’ heading. Other answers will be in the ‘Arguments’ heading.

What is the default parameter for ‘header’ in the

read.csv()function?What argument would you have to change to read a file that was delimited by semicolons (;) rather than commas?

What argument would you have to change to read file in which numbers used commas for decimal separation (i.e. 1,00)?

What argument would you have to change to read in only the first 10,000 rows of a very large file?

The

read.csv()function has the argument ‘header’ set to TRUE by default, this means the function always assumes the first row is header information, (i.e. column names)The

read.csv()function has the argument ‘sep’ set to “,”. This means the function assumes commas are used as delimiters, as you would expect. Changing this parameter (e.g.sep=";") would now interpret semicolons as delimiters.Although it is not listed in the

read.csv()usage,read.csv()is a “version” of the functionread.table()and accepts all its arguments. If you setdec=","you could change the decimal operator. We’d probably assume the delimiter is some other character.You can set

nrowto a numeric value (e.g.nrow=10000) to choose how many rows of a file you read in. This may be useful for very large files where not all the data is needed to test some data cleaning steps you are applying.

Hopefully, this exercise gets you thinking about using the provided help documentation in R. There are many arguments that exist, but which we wont have time to cover. Look here to get familiar with functions you use frequently, you may be surprised at what you find they can do.

Tip: Why does ?read.csv open the documentations to read.table?

The reason for this is because read.csv is actually a

short cut for read.table("file.csv", sep = ","). You can

see in the help documentation that there are several additional

variations of read.table, such as read.csv2 to

read tables separated by ; and read.delim to

read in tables separated by \t (tabs). If you know how your

table is separated, you can use one of the provided short cuts, but case

you run into an unconventional separator you are now equipped with the

knowledge to define it in the sep = argument of

read.table!

Now, let’s read in the file combined_tidy_vcf.csv which

will be located in /home/dcuser/r_data/. Call this data

variants. The first argument to pass to our

read.csv() function is the file path for our data. The file

path must be in quotes and now is a good time to remember to use tab

autocompletion. If you use tab autocompletion you avoid typos

and errors in file paths. Use it!

R

## read in a CSV file and save it as 'variants'

variants <- read.csv("/home/dcuser/r_data/combined_tidy_vcf.csv")

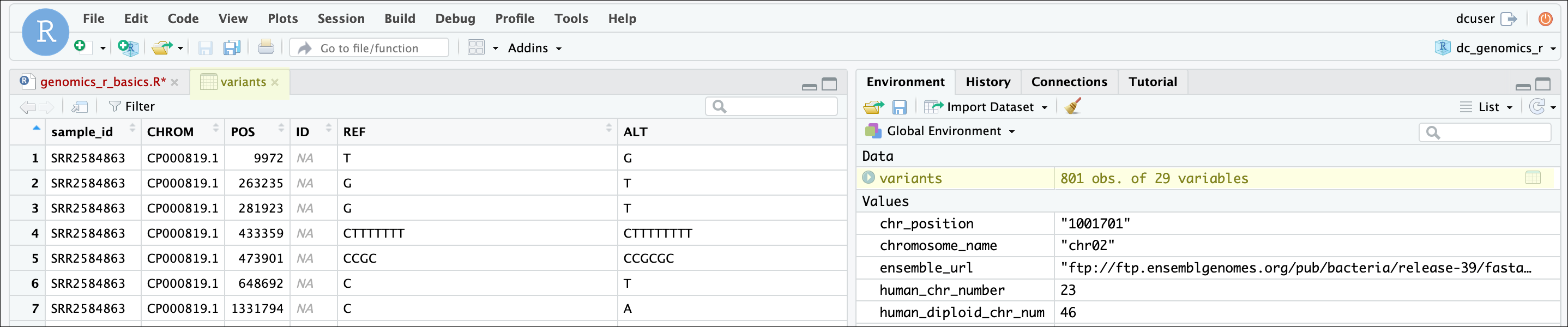

One of the first things you should notice is that in the Environment

window, you have the variants object, listed as 801 obs.

(observations/rows) of 29 variables (columns). Double-clicking on the

name of the object will open a view of the data in a new tab.

The majority of the columns in the data frame correspond to standard fields found in a Variant Call Format (VCF) file, while others were added during our data processing. The VCF format is a standard format for storing variant calls (also known as Single Nucleotide Polymorphisms or SNPs), and you can read more about it, including a description of the fields we have here in the VCF specification or on wikipedia.

We can also quickly query the dimensions of the variable using

dim(). You’ll see that the first number 801

shows the number of rows, then 29 the number of columns

R

## get summary statistics on a data frame

dim(variants)

OUTPUT

[1] 801 29Summarizing, subsetting, and determining the structure of a data frame.

A data frame is the standard way in R to store tabular data. A data frame could also be thought of as a collection of vectors, all of which have the same length. Using only two functions, we can learn a lot about out data frame including some summary statistics as well as well as the “structure” of the data frame. Let’s examine what each of these functions can tell us:

R

## get summary statistics on a data frame

summary(variants)

OUTPUT

sample_id CHROM POS ID

Length:801 Length:801 Min. : 1521 Mode:logical

Class :character Class :character 1st Qu.:1115970 NA's:801

Mode :character Mode :character Median :2290361

Mean :2243682

3rd Qu.:3317082

Max. :4629225

REF ALT QUAL FILTER

Length:801 Length:801 Min. : 4.385 Mode:logical

Class :character Class :character 1st Qu.:139.000 NA's:801

Mode :character Mode :character Median :195.000

Mean :172.276

3rd Qu.:225.000

Max. :228.000

INDEL IDV IMF DP

Mode :logical Min. : 2.000 Min. :0.5714 Min. : 2.00

FALSE:700 1st Qu.: 7.000 1st Qu.:0.8823 1st Qu.: 7.00

TRUE :101 Median : 9.000 Median :1.0000 Median :10.00

Mean : 9.396 Mean :0.9219 Mean :10.57

3rd Qu.:11.000 3rd Qu.:1.0000 3rd Qu.:13.00

Max. :20.000 Max. :1.0000 Max. :79.00

NA's :700 NA's :700

VDB RPB MQB BQB

Min. :0.0005387 Min. :0.0000 Min. :0.0000 Min. :0.1153

1st Qu.:0.2180410 1st Qu.:0.3776 1st Qu.:0.1070 1st Qu.:0.6963

Median :0.4827410 Median :0.8663 Median :0.2872 Median :0.8615

Mean :0.4926291 Mean :0.6970 Mean :0.5330 Mean :0.7784

3rd Qu.:0.7598940 3rd Qu.:1.0000 3rd Qu.:1.0000 3rd Qu.:1.0000

Max. :0.9997130 Max. :1.0000 Max. :1.0000 Max. :1.0000

NA's :773 NA's :773 NA's :773

MQSB SGB MQ0F ICB

Min. :0.01348 Min. :-0.6931 Min. :0.00000 Mode:logical

1st Qu.:0.95494 1st Qu.:-0.6762 1st Qu.:0.00000 NA's:801

Median :1.00000 Median :-0.6620 Median :0.00000

Mean :0.96428 Mean :-0.6444 Mean :0.01127

3rd Qu.:1.00000 3rd Qu.:-0.6364 3rd Qu.:0.00000

Max. :1.01283 Max. :-0.4536 Max. :0.66667

NA's :48

HOB AC AN DP4 MQ

Mode:logical Min. :1 Min. :1 Length:801 Min. :10.00

NA's:801 1st Qu.:1 1st Qu.:1 Class :character 1st Qu.:60.00

Median :1 Median :1 Mode :character Median :60.00

Mean :1 Mean :1 Mean :58.19

3rd Qu.:1 3rd Qu.:1 3rd Qu.:60.00

Max. :1 Max. :1 Max. :60.00

Indiv gt_PL gt_GT gt_GT_alleles

Length:801 Length:801 Min. :1 Length:801

Class :character Class :character 1st Qu.:1 Class :character

Mode :character Mode :character Median :1 Mode :character

Mean :1

3rd Qu.:1

Max. :1

Our data frame had 29 variables, so we get 29 fields that summarize

the data. The QUAL, IMF, and VDB

variables (and several others) are numerical data and so you get summary

statistics on the min and max values for these columns, as well as mean,

median, and interquartile ranges. Many of the other variables

(e.g. sample_id) are treated as characters data (more on

this in a bit).

There is a lot to work with, so we will subset the columns into a new

data frame using the data.frame() function. To subset/index

a two dimensional variable, we need to define them on the appropriate

side of the brackets. The left hand side of the comma indicates the rows

you want to subset, and the right is the column position (e.g. [“row

index”, “column index”]).

Let’s put the columns 1, 2, 3, and 6 into a new data frame called subset:

R

## Notice that we are wrapping the numbers in a c() function, to indicate a vector

## in the right hand side of the comma.

subset <- data.frame(variants[, c(1:3, 6)])

Now, let’s use the str() (structure) function to look a

little more closely at how data frames work:

R

## get the structure of a data frame

str(subset)

OUTPUT

'data.frame': 801 obs. of 4 variables:

$ sample_id: chr "SRR2584863" "SRR2584863" "SRR2584863" "SRR2584863" ...

$ CHROM : chr "CP000819.1" "CP000819.1" "CP000819.1" "CP000819.1" ...

$ POS : int 9972 263235 281923 433359 473901 648692 1331794 1733343 2103887 2333538 ...

$ ALT : chr "G" "T" "T" "CTTTTTTTT" ...Ok, that’s a lot up unpack! Some things to notice.

The object type

data.frameis displayed in the first row along with its dimensions, in this case 801 observations (rows) and 4 variables (columns)Each variable (column) has a name (e.g.

sample_id). Notice that before each variable name there is a$- this will be important later.-

Each variable name is followed by the data type it contains (e.g. chr, int, etc.). The

inttype shows an integer, which is a type of numerical data, where it can only store whole numbers (i.e. no decimal points ).ChallengeExercise: Revisiting modes and classes

Remember when we said mode and class are sometimes different? If you do, here is a chance to check. What happens when you try the following?

mode(variants)class(variants)

R

mode(variants)OUTPUT

[1] "list"R

class(variants)OUTPUT

[1] "data.frame"This result makes sense because

mode()(which deals with how an object is stored) tells us thatvariantsis treated as a list in R. A data frame is in some sense a “fancy” list. However, data frames do have some specific properties beyond that of a basic list, so they have their own class (data.frame), which is important for functions (and programmers) to know.

Introducing Factors

Factors are the final major data structure we will introduce in our R genomics lessons. Factors can be thought of as vectors which are specialized for categorical data. Given R’s specialization for statistics, this make sense since categorical and continuous variables are usually treated differently. Sometimes you may want to have data treated as a factor, but in other cases, this may be undesirable.

Let’s explore the value of treating some vectors that are categorical

in nature as factors. To do this we’ll take a look at just the alternate

alleles. We can use the $ operator to access or extract a

column by its name in data frames (or to extract objects within named

lists).

R

## extract the "ALT" column to a new object

alt_alleles <- subset$ALT

Let’s look at the first few items in our factor using

head():

R

head(alt_alleles)

OUTPUT

[1] "G" "T" "T" "CTTTTTTTT" "CCGCGC" "T" There are 801 alleles (one for each row). To simplify, lets look at just the single-nucleotide alleles (SNPs).

Let’s review some of the vector indexing skills from the last episode that can help:

R

# This will find all matching alleles with the single nucleotide "A" and provide a TRUE/FASE vector

alt_alleles == "A"

OUTPUT

[1] FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE TRUE TRUE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE

[13] FALSE FALSE TRUE FALSE TRUE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE

[25] FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE TRUE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE

[37] TRUE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE TRUE TRUE FALSE FALSE FALSE

[49] FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE

[61] FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE TRUE TRUE FALSE FALSE FALSE

[73] FALSE TRUE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE

[85] FALSE TRUE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE

[97] FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE TRUE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE

[109] FALSE FALSE FALSE TRUE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE

[121] FALSE FALSE FALSE TRUE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE

[133] FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE

[145] FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE

[157] FALSE FALSE TRUE FALSE FALSE FALSE TRUE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE

[169] FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE

[181] FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE TRUE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE

[193] TRUE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE

[205] FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE TRUE FALSE FALSE

[217] FALSE FALSE TRUE FALSE FALSE FALSE TRUE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE

[229] FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE TRUE FALSE

[241] FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE

[253] FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE TRUE FALSE TRUE TRUE FALSE FALSE FALSE

[265] FALSE TRUE TRUE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE

[277] TRUE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE TRUE FALSE FALSE FALSE TRUE

[289] FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE TRUE FALSE TRUE TRUE FALSE FALSE

[301] FALSE TRUE FALSE TRUE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE TRUE FALSE TRUE

[313] FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE TRUE FALSE TRUE TRUE FALSE FALSE TRUE FALSE

[325] FALSE TRUE TRUE TRUE TRUE TRUE TRUE FALSE TRUE FALSE FALSE TRUE

[337] FALSE FALSE TRUE FALSE FALSE TRUE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE

[349] FALSE TRUE TRUE TRUE FALSE TRUE FALSE FALSE FALSE TRUE FALSE FALSE

[361] FALSE FALSE FALSE TRUE TRUE TRUE TRUE FALSE TRUE FALSE FALSE FALSE

[373] FALSE FALSE FALSE TRUE FALSE TRUE FALSE FALSE TRUE FALSE FALSE TRUE

[385] FALSE FALSE FALSE TRUE FALSE TRUE FALSE TRUE FALSE FALSE FALSE TRUE

[397] TRUE FALSE TRUE TRUE TRUE FALSE FALSE TRUE TRUE FALSE FALSE TRUE

[409] FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE TRUE FALSE FALSE FALSE TRUE TRUE FALSE

[421] FALSE TRUE FALSE TRUE TRUE FALSE TRUE FALSE TRUE FALSE FALSE FALSE

[433] TRUE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE TRUE TRUE FALSE FALSE FALSE

[445] TRUE TRUE TRUE TRUE FALSE TRUE TRUE TRUE FALSE TRUE FALSE TRUE

[457] TRUE TRUE FALSE TRUE FALSE TRUE FALSE FALSE TRUE TRUE TRUE TRUE

[469] TRUE TRUE FALSE FALSE TRUE TRUE TRUE TRUE FALSE FALSE FALSE TRUE

[481] FALSE FALSE TRUE FALSE TRUE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE

[493] TRUE FALSE FALSE FALSE TRUE TRUE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE TRUE TRUE

[505] TRUE TRUE TRUE TRUE FALSE FALSE FALSE TRUE FALSE TRUE FALSE FALSE

[517] FALSE FALSE FALSE TRUE TRUE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE TRUE FALSE

[529] FALSE FALSE TRUE FALSE FALSE TRUE FALSE FALSE TRUE TRUE TRUE FALSE

[541] TRUE FALSE FALSE TRUE FALSE TRUE TRUE TRUE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE

[553] FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE TRUE TRUE FALSE FALSE FALSE TRUE TRUE TRUE

[565] FALSE TRUE FALSE TRUE TRUE TRUE FALSE TRUE TRUE FALSE FALSE TRUE

[577] FALSE FALSE TRUE TRUE FALSE TRUE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE

[589] FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE TRUE FALSE FALSE FALSE TRUE

[601] FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE TRUE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE

[613] FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE TRUE FALSE TRUE FALSE TRUE TRUE FALSE

[625] TRUE TRUE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE TRUE TRUE FALSE FALSE FALSE

[637] FALSE FALSE FALSE TRUE TRUE TRUE FALSE TRUE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE

[649] TRUE TRUE TRUE FALSE FALSE FALSE TRUE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE

[661] FALSE FALSE FALSE TRUE TRUE TRUE TRUE FALSE FALSE TRUE FALSE FALSE

[673] TRUE FALSE TRUE FALSE TRUE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE

[685] FALSE TRUE TRUE FALSE TRUE FALSE TRUE TRUE FALSE FALSE TRUE TRUE

[697] TRUE FALSE FALSE TRUE TRUE TRUE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE

[709] FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE TRUE TRUE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE

[721] FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE TRUE FALSE FALSE TRUE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE

[733] TRUE FALSE TRUE FALSE FALSE TRUE TRUE FALSE TRUE FALSE TRUE FALSE

[745] FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE TRUE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE TRUE TRUE

[757] FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE TRUE FALSE FALSE

[769] FALSE TRUE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE TRUE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE TRUE

[781] FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE TRUE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE

[793] TRUE TRUE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSER

# Then, we wrap them into an index to pull all the positions that match this.

alt_alleles[alt_alleles == "A"]

OUTPUT

[1] "A" "A" "A" "A" "A" "A" "A" "A" "A" "A" "A" "A" "A" "A" "A" "A" "A" "A"

[19] "A" "A" "A" "A" "A" "A" "A" "A" "A" "A" "A" "A" "A" "A" "A" "A" "A" "A"

[37] "A" "A" "A" "A" "A" "A" "A" "A" "A" "A" "A" "A" "A" "A" "A" "A" "A" "A"

[55] "A" "A" "A" "A" "A" "A" "A" "A" "A" "A" "A" "A" "A" "A" "A" "A" "A" "A"

[73] "A" "A" "A" "A" "A" "A" "A" "A" "A" "A" "A" "A" "A" "A" "A" "A" "A" "A"

[91] "A" "A" "A" "A" "A" "A" "A" "A" "A" "A" "A" "A" "A" "A" "A" "A" "A" "A"

[109] "A" "A" "A" "A" "A" "A" "A" "A" "A" "A" "A" "A" "A" "A" "A" "A" "A" "A"

[127] "A" "A" "A" "A" "A" "A" "A" "A" "A" "A" "A" "A" "A" "A" "A" "A" "A" "A"

[145] "A" "A" "A" "A" "A" "A" "A" "A" "A" "A" "A" "A" "A" "A" "A" "A" "A" "A"

[163] "A" "A" "A" "A" "A" "A" "A" "A" "A" "A" "A" "A" "A" "A" "A" "A" "A" "A"

[181] "A" "A" "A" "A" "A" "A" "A" "A" "A" "A" "A" "A" "A" "A" "A" "A" "A" "A"

[199] "A" "A" "A" "A" "A" "A" "A" "A" "A" "A" "A" "A" "A"R

# If we repeat this for each nucleotide A, T, G, and C, and connect them using `c()`,

# we can index all the single nucleotide changes.

snps <- c(alt_alleles[alt_alleles == "A"],

alt_alleles[alt_alleles=="T"],

alt_alleles[alt_alleles=="G"],

alt_alleles[alt_alleles=="C"])

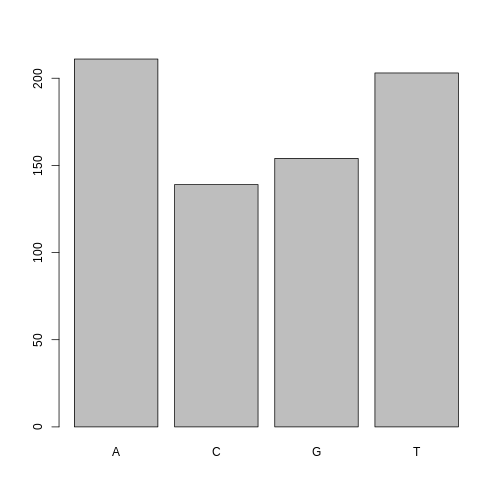

This leaves us with a vector of the 701 alternative alleles which were single nucleotides. Right now, they are being treated a characters, but we could treat them as categories of SNP. Doing this will enable some nice features. For example, we can try to generate a plot of this character vector as it is right now:

R

plot(snps)

WARNING

Warning in xy.coords(x, y, xlabel, ylabel, log): NAs introduced by coercionWARNING

Warning in min(x): no non-missing arguments to min; returning InfWARNING

Warning in max(x): no non-missing arguments to max; returning -InfERROR

Error in `plot.window()`:

! need finite 'ylim' valuesWhoops! Though the plot() function will do its best to

give us a quick plot, it is unable to do so here. Let’s use

str() to see why this might be:

R

str(snps)

OUTPUT

chr [1:707] "A" "A" "A" "A" "A" "A" "A" "A" "A" "A" "A" "A" "A" "A" "A" ...R may not know how to plot a character vector! One way to fix this it

to tell R to treat the SNPs as categories (i.e. a factor vector); we

will create a new object to avoid confusion using the

factor() function:

R

factor_snps <- factor(snps)

Let’s learn a little more about this new type of vector:

R

str(factor_snps)

OUTPUT

Factor w/ 4 levels "A","C","G","T": 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 ...What we get back are the categories (“A”,“C”,“G”,“T”) in our factor; these are called “Levels”. Levels are the different categories contained in a factor. By default, R will organize the levels in a factor in alphabetical order. So the first level in this factor is “A”.

For the sake of efficiency, R stores the content of a factor as a

vector of integers, which an integer is assigned to each of the possible

levels. Recall levels are assigned in alphabetical order. In this case,

the first item in our factor_snps object is “A”, which

happens to be the 1st level of our factor, ordered alphabetically. This

explains the sequence of “1”s (“Factor w/ 4 levels”A”,“C”,“G”,“T”: 1 1 1

1 1 1 1 1 1 1 …“), since”A” is the first level, and the first few items

in our factor are all “A”s.

We can see how many items in our vector fall into each category:

R

summary(factor_snps)

OUTPUT

A C G T

211 139 154 203 R

# Compare the character vector

summary(snps)

OUTPUT

Length Class Mode

707 character character As you can imagine, factors are already useful when you want to generate a tally.

Tip: treating objects as categories without changing their mode

You don’t have to make an object a factor to get the benefits of

treating an object as a factor. See what happens when you use the

as.factor() function on factor_snps. To

generate a tally, you can sometimes also use the table()

function; though sometimes you may need to combine both (i.e.

table(as.factor(object)))

Plotting and ordering factors

One of the most common uses for factors will be when you plot categorical values. For example, suppose we want to know how many of our variants had each possible SNP we could generate a plot:

R

plot(factor_snps)

This isn’t a particularly pretty example of a plot but it works. We’ll be learning much more about creating nice, publication-quality graphics later in this lesson.

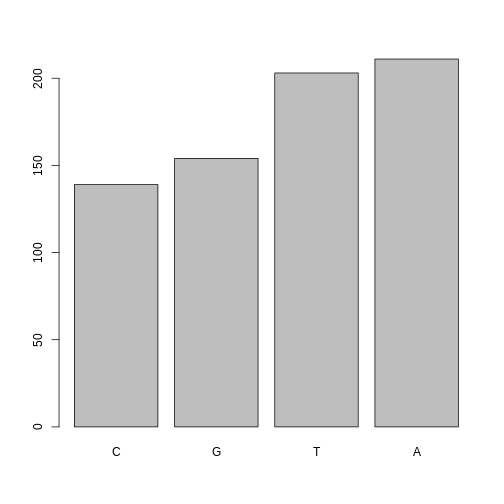

If you recall, factors are ordered alphabetically. That might make sense, but categories (e.g., “red”, “blue”, “green”) often do not have an intrinsic order. What if we wanted to order our plot according to the numerical value (i.e., in descending order of SNP frequency)? We can enforce an order on our factors:

R

ordered_factor_snps <- factor(factor_snps, levels = names(sort(table(factor_snps))))

Let’s deconstruct this from the inside out (you can try each of these commands to see why this works):

- We create a table of

factor_snpsto get the frequency of each SNP:table(factor_snps) - We sort this table:

sort(table(factor_snps)); use thedecreasing =parameter for this function if you wanted to change from the default of FALSE - Using the

namesfunction gives us just the character names of the table sorted by frequencies:names(sort(table(factor_snps))) - The

factorfunction is what allows us to create a factor. We give it thefactor_snpsobject as input, and use thelevels=parameter to enforce the ordering of the levels.

Now we see our plot has be reordered:

R

plot(ordered_factor_snps)

Factors come in handy in many places when using R. Even using more sophisticated plotting packages such as ggplot2 will sometimes require you to understand how to manipulate factors.

Tip: Packages in R – what are they and why do we use them?

Packages are simply collections of functions and/or data that can be

used to extend the capabilities of R beyond the core functionality that

comes with it by default. The default set of functions and packages that

come ‘in the box’ when you install R for the first time on a given

computer are called ‘base R’. However, one of the major benefits of

using an open source programming language is that there are thousands of

useful R packages freely available that span all types of statistical

analysis, data visualization, and more. The main place that these

additional R packages are made available is from a website called the

Comprehensive R Archive Network (CRAN). When you use the built-in

R function install.packages(), it will look on CRAN for the

package and install it on your computer. So, for example, to install

packages such as dplyr and ggplot2 (which

you’ll do in the next few lessons), you would use the following

command:

R

# install a package from CRAN

install.packages("ggplot2")

OUTPUT

The following package(s) will be installed:

- ggplot2 [4.0.2]

These packages will be installed into "/__w/genomics-r-intro/genomics-r-intro/renv/profiles/lesson-requirements/renv/library/linux-ubuntu-noble/R-4.5/x86_64-pc-linux-gnu".

# Installing packages --------------------------------------------------------

- Installing ggplot2 4.0.2 ... OK [linked from cache]

Successfully installed 1 package in 12 milliseconds.R

install.packages("dplyr")

OUTPUT

The following package(s) will be installed:

- dplyr [1.2.0]

These packages will be installed into "/__w/genomics-r-intro/genomics-r-intro/renv/profiles/lesson-requirements/renv/library/linux-ubuntu-noble/R-4.5/x86_64-pc-linux-gnu".

# Installing packages --------------------------------------------------------

- Installing dplyr 1.2.0 ... OK [linked from cache]

Successfully installed 1 package in 5.4 milliseconds.These two packages are among the most popular add on packages used in R, and they are part of a large set of very useful packages called the tidyverse. Packages in the tidyverse are designed to work well together and are made to work with tidy data (which we described earlier in this lesson).

Subsetting data frames

Next, we are going to talk about how you can get specific values from data frames, and where necessary, change the mode of a column of values.

The first thing to remember is that a data frame is two-dimensional

(rows and columns). Therefore, to select a specific value we will will

once again use [] (bracket) notation, but we will specify

more than one value (except in some cases where we are taking a

range).

Exercise: Subsetting a data frame

Try the following indices and functions and try to figure out what they return

variants[1,1]variants[2,4]variants[801,29]variants[2, ]variants[-1, ]variants[1:4,1]variants[1:10,c("REF","ALT")]variants[,c("sample_id")]head(variants)tail(variants)variants$sample_idvariants[variants$REF == "A",]

R

variants[1, 1]

OUTPUT

[1] "SRR2584863"R

variants[2, 4]

OUTPUT

[1] NAR

variants[801, 29]

OUTPUT

[1] "T"R

variants[2, ]

OUTPUT

sample_id CHROM POS ID REF ALT QUAL FILTER INDEL IDV IMF DP VDB

2 SRR2584863 CP000819.1 263235 NA G T 85 NA FALSE NA NA 6 0.096133

RPB MQB BQB MQSB SGB MQ0F ICB HOB AC AN DP4 MQ

2 1 1 1 NA -0.590765 0.166667 NA NA 1 1 0,1,0,5 33

Indiv gt_PL

2 /home/dcuser/dc_workshop/results/bam/SRR2584863.aligned.sorted.bam 112,0

gt_GT gt_GT_alleles

2 1 TR

variants[-1, ]

OUTPUT

sample_id CHROM POS ID REF ALT QUAL FILTER INDEL IDV IMF

2 SRR2584863 CP000819.1 263235 NA G T 85 NA FALSE NA NA

3 SRR2584863 CP000819.1 281923 NA G T 217 NA FALSE NA NA

4 SRR2584863 CP000819.1 433359 NA CTTTTTTT CTTTTTTTT 64 NA TRUE 12 1.0

5 SRR2584863 CP000819.1 473901 NA CCGC CCGCGC 228 NA TRUE 9 0.9

6 SRR2584863 CP000819.1 648692 NA C T 210 NA FALSE NA NA

7 SRR2584863 CP000819.1 1331794 NA C A 178 NA FALSE NA NA

DP VDB RPB MQB BQB MQSB SGB MQ0F ICB HOB AC AN DP4 MQ

2 6 0.096133 1 1 1 NA -0.590765 0.166667 NA NA 1 1 0,1,0,5 33

3 10 0.774083 NA NA NA 0.974597 -0.662043 0.000000 NA NA 1 1 0,0,4,5 60

4 12 0.477704 NA NA NA 1.000000 -0.676189 0.000000 NA NA 1 1 0,1,3,8 60

5 10 0.659505 NA NA NA 0.916482 -0.662043 0.000000 NA NA 1 1 1,0,2,7 60

6 10 0.268014 NA NA NA 0.916482 -0.670168 0.000000 NA NA 1 1 0,0,7,3 60

7 8 0.624078 NA NA NA 0.900802 -0.651104 0.000000 NA NA 1 1 0,0,3,5 60

Indiv gt_PL

2 /home/dcuser/dc_workshop/results/bam/SRR2584863.aligned.sorted.bam 112,0

3 /home/dcuser/dc_workshop/results/bam/SRR2584863.aligned.sorted.bam 247,0

4 /home/dcuser/dc_workshop/results/bam/SRR2584863.aligned.sorted.bam 91,0

5 /home/dcuser/dc_workshop/results/bam/SRR2584863.aligned.sorted.bam 255,0

6 /home/dcuser/dc_workshop/results/bam/SRR2584863.aligned.sorted.bam 240,0

7 /home/dcuser/dc_workshop/results/bam/SRR2584863.aligned.sorted.bam 208,0

gt_GT gt_GT_alleles

2 1 T

3 1 T

4 1 CTTTTTTTT

5 1 CCGCGC

6 1 T

7 1 AR

variants[1:4, 1]

OUTPUT

[1] "SRR2584863" "SRR2584863" "SRR2584863" "SRR2584863"R

variants[1:10, c("REF", "ALT")]

OUTPUT

REF

1 T

2 G

3 G

4 CTTTTTTT

5 CCGC

6 C

7 C

8 G

9 ACAGCCAGCCAGCCAGCCAGCCAGCCAGCCAG

10 AT

ALT

1 G

2 T

3 T

4 CTTTTTTTT

5 CCGCGC

6 T

7 A

8 A

9 ACAGCCAGCCAGCCAGCCAGCCAGCCAGCCAGCCAGCCAGCCAGCCAGCCAGCCAG

10 ATTR

variants[, c("sample_id")]

OUTPUT

[1] "SRR2584863" "SRR2584863" "SRR2584863" "SRR2584863" "SRR2584863"

[6] "SRR2584863"R

head(variants)

OUTPUT

sample_id CHROM POS ID REF ALT QUAL FILTER INDEL IDV IMF

1 SRR2584863 CP000819.1 9972 NA T G 91 NA FALSE NA NA

2 SRR2584863 CP000819.1 263235 NA G T 85 NA FALSE NA NA

3 SRR2584863 CP000819.1 281923 NA G T 217 NA FALSE NA NA

4 SRR2584863 CP000819.1 433359 NA CTTTTTTT CTTTTTTTT 64 NA TRUE 12 1.0

5 SRR2584863 CP000819.1 473901 NA CCGC CCGCGC 228 NA TRUE 9 0.9

6 SRR2584863 CP000819.1 648692 NA C T 210 NA FALSE NA NA

DP VDB RPB MQB BQB MQSB SGB MQ0F ICB HOB AC AN DP4 MQ

1 4 0.0257451 NA NA NA NA -0.556411 0.000000 NA NA 1 1 0,0,0,4 60

2 6 0.0961330 1 1 1 NA -0.590765 0.166667 NA NA 1 1 0,1,0,5 33

3 10 0.7740830 NA NA NA 0.974597 -0.662043 0.000000 NA NA 1 1 0,0,4,5 60

4 12 0.4777040 NA NA NA 1.000000 -0.676189 0.000000 NA NA 1 1 0,1,3,8 60

5 10 0.6595050 NA NA NA 0.916482 -0.662043 0.000000 NA NA 1 1 1,0,2,7 60

6 10 0.2680140 NA NA NA 0.916482 -0.670168 0.000000 NA NA 1 1 0,0,7,3 60

Indiv gt_PL

1 /home/dcuser/dc_workshop/results/bam/SRR2584863.aligned.sorted.bam 121,0

2 /home/dcuser/dc_workshop/results/bam/SRR2584863.aligned.sorted.bam 112,0

3 /home/dcuser/dc_workshop/results/bam/SRR2584863.aligned.sorted.bam 247,0

4 /home/dcuser/dc_workshop/results/bam/SRR2584863.aligned.sorted.bam 91,0

5 /home/dcuser/dc_workshop/results/bam/SRR2584863.aligned.sorted.bam 255,0

6 /home/dcuser/dc_workshop/results/bam/SRR2584863.aligned.sorted.bam 240,0

gt_GT gt_GT_alleles

1 1 G

2 1 T

3 1 T

4 1 CTTTTTTTT

5 1 CCGCGC

6 1 TR

tail(variants)

OUTPUT

sample_id CHROM POS ID REF ALT QUAL FILTER INDEL IDV IMF DP

796 SRR2589044 CP000819.1 3444175 NA G T 184 NA FALSE NA NA 9

797 SRR2589044 CP000819.1 3481820 NA A G 225 NA FALSE NA NA 12

798 SRR2589044 CP000819.1 3893550 NA AG AGG 101 NA TRUE 4 1 4

799 SRR2589044 CP000819.1 3901455 NA A AC 70 NA TRUE 3 1 3

800 SRR2589044 CP000819.1 4100183 NA A G 177 NA FALSE NA NA 8

801 SRR2589044 CP000819.1 4431393 NA TGG T 225 NA TRUE 10 1 10

VDB RPB MQB BQB MQSB SGB MQ0F ICB HOB AC AN DP4 MQ

796 0.4714620 NA NA NA 0.992367 -0.651104 0 NA NA 1 1 0,0,4,4 60

797 0.8707240 NA NA NA 1.000000 -0.680642 0 NA NA 1 1 0,0,4,8 60

798 0.9182970 NA NA NA 1.000000 -0.556411 0 NA NA 1 1 0,0,3,1 52

799 0.0221621 NA NA NA NA -0.511536 0 NA NA 1 1 0,0,3,0 60

800 0.9272700 NA NA NA 0.900802 -0.651104 0 NA NA 1 1 0,0,3,5 60

801 0.7488140 NA NA NA 1.007750 -0.670168 0 NA NA 1 1 0,0,4,6 60

Indiv gt_PL

796 /home/dcuser/dc_workshop/results/bam/SRR2589044.aligned.sorted.bam 214,0

797 /home/dcuser/dc_workshop/results/bam/SRR2589044.aligned.sorted.bam 255,0

798 /home/dcuser/dc_workshop/results/bam/SRR2589044.aligned.sorted.bam 131,0

799 /home/dcuser/dc_workshop/results/bam/SRR2589044.aligned.sorted.bam 100,0

800 /home/dcuser/dc_workshop/results/bam/SRR2589044.aligned.sorted.bam 207,0

801 /home/dcuser/dc_workshop/results/bam/SRR2589044.aligned.sorted.bam 255,0

gt_GT gt_GT_alleles

796 1 T

797 1 G

798 1 AGG

799 1 AC

800 1 G

801 1 TR

variants$sample_id

OUTPUT

[1] "SRR2584863" "SRR2584863" "SRR2584863" "SRR2584863" "SRR2584863"

[6] "SRR2584863"R

variants[variants$REF == "A", ]

OUTPUT

sample_id CHROM POS ID REF ALT QUAL FILTER INDEL IDV IMF DP

11 SRR2584863 CP000819.1 2407766 NA A C 104 NA FALSE NA NA 9

12 SRR2584863 CP000819.1 2446984 NA A C 225 NA FALSE NA NA 20

14 SRR2584863 CP000819.1 2665639 NA A T 225 NA FALSE NA NA 19

16 SRR2584863 CP000819.1 3339313 NA A C 211 NA FALSE NA NA 10

18 SRR2584863 CP000819.1 3481820 NA A G 200 NA FALSE NA NA 9

19 SRR2584863 CP000819.1 3488669 NA A C 225 NA FALSE NA NA 13

VDB RPB MQB BQB MQSB SGB MQ0F ICB HOB AC

11 0.0230738 0.900802 0.150134 0.750668 0.500000 -0.590765 0.333333 NA NA 1

12 0.0714027 NA NA NA 1.000000 -0.689466 0.000000 NA NA 1

14 0.9960390 NA NA NA 1.000000 -0.690438 0.000000 NA NA 1

16 0.4059360 NA NA NA 1.007750 -0.670168 0.000000 NA NA 1

18 0.1070810 NA NA NA 0.974597 -0.662043 0.000000 NA NA 1

19 0.0162706 NA NA NA 1.000000 -0.680642 0.000000 NA NA 1

AN DP4 MQ

11 1 3,0,3,2 25

12 1 0,0,10,6 60

14 1 0,0,12,5 60

16 1 0,0,4,6 60

18 1 0,0,4,5 60

19 1 0,0,8,4 60

Indiv gt_PL

11 /home/dcuser/dc_workshop/results/bam/SRR2584863.aligned.sorted.bam 131,0

12 /home/dcuser/dc_workshop/results/bam/SRR2584863.aligned.sorted.bam 255,0

14 /home/dcuser/dc_workshop/results/bam/SRR2584863.aligned.sorted.bam 255,0

16 /home/dcuser/dc_workshop/results/bam/SRR2584863.aligned.sorted.bam 241,0

18 /home/dcuser/dc_workshop/results/bam/SRR2584863.aligned.sorted.bam 230,0

19 /home/dcuser/dc_workshop/results/bam/SRR2584863.aligned.sorted.bam 255,0

gt_GT gt_GT_alleles

11 1 C

12 1 C

14 1 T

16 1 C

18 1 G

19 1 CThe subsetting notation is very similar to what we learned for vectors. The key differences include:

- Typically provide two values separated by commas: data.frame[row, column]

- In cases where you are taking a continuous range of numbers use a colon between the numbers (start:stop, inclusive)

- For a non continuous set of numbers, pass a vector using

c() - Index using the name of a column(s) by passing them as vectors using

c()

Finally, in all of the subsetting exercises above, we printed values to the screen. You can create a new data frame object by assigning them to a new object name:

R

# create a new data frame containing only observations from SRR2584863

SRR2584863_variants <- variants[variants$sample_id == "SRR2584863", ]

# check the dimension of the data frame

dim(SRR2584863_variants)

OUTPUT

[1] 25 29R

# get a summary of the data frame

summary(SRR2584863_variants)

OUTPUT

sample_id CHROM POS ID

Length:25 Length:25 Min. : 9972 Mode:logical

Class :character Class :character 1st Qu.:1331794 NA's:25

Mode :character Mode :character Median :2618472

Mean :2464989

3rd Qu.:3488669

Max. :4616538

REF ALT QUAL FILTER

Length:25 Length:25 Min. : 31.89 Mode:logical

Class :character Class :character 1st Qu.:104.00 NA's:25

Mode :character Mode :character Median :211.00

Mean :172.97

3rd Qu.:225.00

Max. :228.00

INDEL IDV IMF DP

Mode :logical Min. : 2.00 Min. :0.6667 Min. : 2.0

FALSE:19 1st Qu.: 3.25 1st Qu.:0.9250 1st Qu.: 9.0

TRUE :6 Median : 8.00 Median :1.0000 Median :10.0

Mean : 7.00 Mean :0.9278 Mean :10.4

3rd Qu.: 9.75 3rd Qu.:1.0000 3rd Qu.:12.0

Max. :12.00 Max. :1.0000 Max. :20.0

NA's :19 NA's :19

VDB RPB MQB BQB

Min. :0.01627 Min. :0.9008 Min. :0.04979 Min. :0.7507

1st Qu.:0.07140 1st Qu.:0.9275 1st Qu.:0.09996 1st Qu.:0.7627

Median :0.37674 Median :0.9542 Median :0.15013 Median :0.7748

Mean :0.40429 Mean :0.9517 Mean :0.39997 Mean :0.8418

3rd Qu.:0.65951 3rd Qu.:0.9771 3rd Qu.:0.57507 3rd Qu.:0.8874

Max. :0.99604 Max. :1.0000 Max. :1.00000 Max. :1.0000

NA's :22 NA's :22 NA's :22

MQSB SGB MQ0F ICB

Min. :0.5000 Min. :-0.6904 Min. :0.00000 Mode:logical

1st Qu.:0.9599 1st Qu.:-0.6762 1st Qu.:0.00000 NA's:25

Median :0.9962 Median :-0.6620 Median :0.00000

Mean :0.9442 Mean :-0.6341 Mean :0.04667

3rd Qu.:1.0000 3rd Qu.:-0.6168 3rd Qu.:0.00000

Max. :1.0128 Max. :-0.4536 Max. :0.66667

NA's :3

HOB AC AN DP4 MQ

Mode:logical Min. :1 Min. :1 Length:25 Min. :10.00

NA's:25 1st Qu.:1 1st Qu.:1 Class :character 1st Qu.:60.00

Median :1 Median :1 Mode :character Median :60.00

Mean :1 Mean :1 Mean :55.52

3rd Qu.:1 3rd Qu.:1 3rd Qu.:60.00

Max. :1 Max. :1 Max. :60.00

Indiv gt_PL gt_GT gt_GT_alleles

Length:25 Length:25 Min. :1 Length:25

Class :character Class :character 1st Qu.:1 Class :character

Mode :character Mode :character Median :1 Mode :character

Mean :1

3rd Qu.:1

Max. :1

Coercing values in data frames

Tip: coercion isn’t limited to data frames

While we are going to address coercion in the context of data frames most of these methods apply to other data structures, such as vectors

Sometimes, it is possible that R will misinterpret the type of data represented in a data frame, or store that data in a mode which prevents you from operating on the data the way you wish. For example, a long list of gene names isn’t usually thought of as a categorical variable, the way that your experimental condition (e.g. control, treatment) might be. More importantly, some R packages you use to analyze your data may expect characters as input, not factors. At other times (such as plotting or some statistical analyses) a factor may be more appropriate. Ultimately, you should know how to change the mode of an object.

First, its very important to recognize that coercion happens in R all the time. This can be a good thing when R gets it right, or a bad thing when the result is not what you expect. Consider:

R

snp_chromosomes <- c('3', '11', 'X', '6')

typeof(snp_chromosomes)

OUTPUT

[1] "character"Although there are several numbers in our vector, they are all in quotes, so we have explicitly told R to consider them as characters. However, even if we removed the quotes from the numbers, R would coerce everything into a character:

R

snp_chromosomes_2 <- c(3, 11, 'X', 6)

typeof(snp_chromosomes_2)

OUTPUT

[1] "character"R

snp_chromosomes_2[1]

OUTPUT

[1] "3"We can use the as. functions to explicitly coerce values

from one form into another. Consider the following vector of characters,

which all happen to be valid numbers:

R

snp_positions_2 <- c("8762685", "66560624", "67545785", "154039662")

typeof(snp_positions_2)

OUTPUT

[1] "character"R

snp_positions_2[1]

OUTPUT

[1] "8762685"Now we can coerce snp_positions_2 into a numeric type

using as.numeric():

R

snp_positions_2 <- as.numeric(snp_positions_2)

typeof(snp_positions_2)

OUTPUT

[1] "double"R

snp_positions_2[1]

OUTPUT

[1] 8762685Sometimes coercion is straight forward, but what would happen if we

tried using as.numeric() on

snp_chromosomes_2

R

snp_chromosomes_2 <- as.numeric(snp_chromosomes_2)

WARNING

Warning: NAs introduced by coercionIf we check, we will see that an NA value (R’s default

value for missing data) has been introduced.

R

snp_chromosomes_2

OUTPUT

[1] 3 11 NA 6Trouble can really start when we try to coerce a factor. For example,

when we try to coerce the factor_snps vector into a numeric

mode look at the result:

R

as.numeric(factor_snps)

OUTPUT

[1] 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1

[38] 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1

[75] 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1

[112] 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1

[149] 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1

[186] 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 4

[223] 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 4

[260] 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 4

[297] 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 4

[334] 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 4

[371] 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 4

[408] 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3

[445] 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3

[482] 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3

[519] 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3

[556] 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2

[593] 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2

[630] 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2

[667] 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2

[704] 2 2 2 2Strangely, it works! Almost. Instead of giving an error message, R returns numeric values, which in this case are the integers assigned to the levels in this factor. This kind of behavior can lead to hard-to-find bugs, for example when we do have numbers in a factor, and we get numbers from a coercion. If we don’t look carefully, we may not notice a problem.

If you need to coerce an entire column you can overwrite it using an expression like this one:

R

# make the 'REF' column a character type column

variants$REF <- as.character(variants$REF)

# check the type of the column

typeof(variants$REF)

OUTPUT

[1] "character"StringsAsFactors = ?

Lets summarize this section on coercion with a few take home messages.

- When you explicitly coerce one data type into another (this is known as explicit coercion), be careful to check the result. Ideally, you should try to see if its possible to avoid steps in your analysis that force you to coerce.

- R will sometimes coerce without you asking for it. This is called (appropriately) implicit coercion. For example when we tried to create a vector with multiple data types, R chose one type through implicit coercion.

- Check the structure (

str()) of your data frames before working with them!

Tip: coercion isn’t limited to data frames

Prior to R 4.0 when importing a data frame using any one of the

read.table() functions such as read.csv() ,

the argument StringsAsFactors was by default set to true

TRUE. Setting it to FALSE will treat any non-numeric column to a

character type. read.csv() documentation, you will also see

you can explicitly type your columns using the colClasses

argument. Other R packages (such as the Tidyverse “readr”) don’t have

this particular conversion issue, but many packages will still try to

guess a data type.

Data frame bonus material: math, sorting, renaming

Here are a few operations that don’t need much explanation, but which are good to know.

There are lots of arithmetic functions you may want to apply to your data frame, covering those would be a course in itself (there is some starting material in the Loops in R episode of one of the Software Carpentry lessons). Our lessons will cover some additional summary statistical functions in a subsequent lesson, but overall we will focus on data cleaning and visualization.

You can use functions like mean(), min(),

max() on an individual column. Let’s look at the “DP” or

filtered depth. This value shows the number of filtered reads that

support each of the reported variants.

R

max(variants$DP)

OUTPUT

[1] 79You can sort a data frame using the order()

function:

R

sorted_by_DP <- variants[order(variants$DP), ]

head(sorted_by_DP$DP)

OUTPUT

[1] 2 2 2 2 2 2Exercise

The order() function lists values in increasing order by

default. Look at the documentation for this function and change

sorted_by_DP to start with variants with the greatest

filtered depth (“DP”).

R

sorted_by_DP <- variants[order(variants$DP, decreasing = TRUE), ]

head(sorted_by_DP$DP)

OUTPUT

[1] 79 46 41 29 29 27You can rename columns:

R

colnames(variants)[colnames(variants) == "sample_id"] <- "strain"

# check the column name (hint names are returned as a vector)

colnames(variants)

OUTPUT

[1] "strain" "CHROM" "POS" "ID"

[5] "REF" "ALT" "QUAL" "FILTER"

[9] "INDEL" "IDV" "IMF" "DP"

[13] "VDB" "RPB" "MQB" "BQB"

[17] "MQSB" "SGB" "MQ0F" "ICB"

[21] "HOB" "AC" "AN" "DP4"

[25] "MQ" "Indiv" "gt_PL" "gt_GT"

[29] "gt_GT_alleles"Saving your data frame to a file

We can save data to a file. We will save our

SRR2584863_variants object to a .csv file using the

write.csv() function:

R

write.csv(SRR2584863_variants, file = "data/SRR2584863_variants.csv")

The write.csv() function has some additional arguments

listed in the help, but at a minimum you need to tell it what data frame

to write to file, and give a path to a file name in quotes (if you only

provide a file name, the file will be written in the current working

directory).

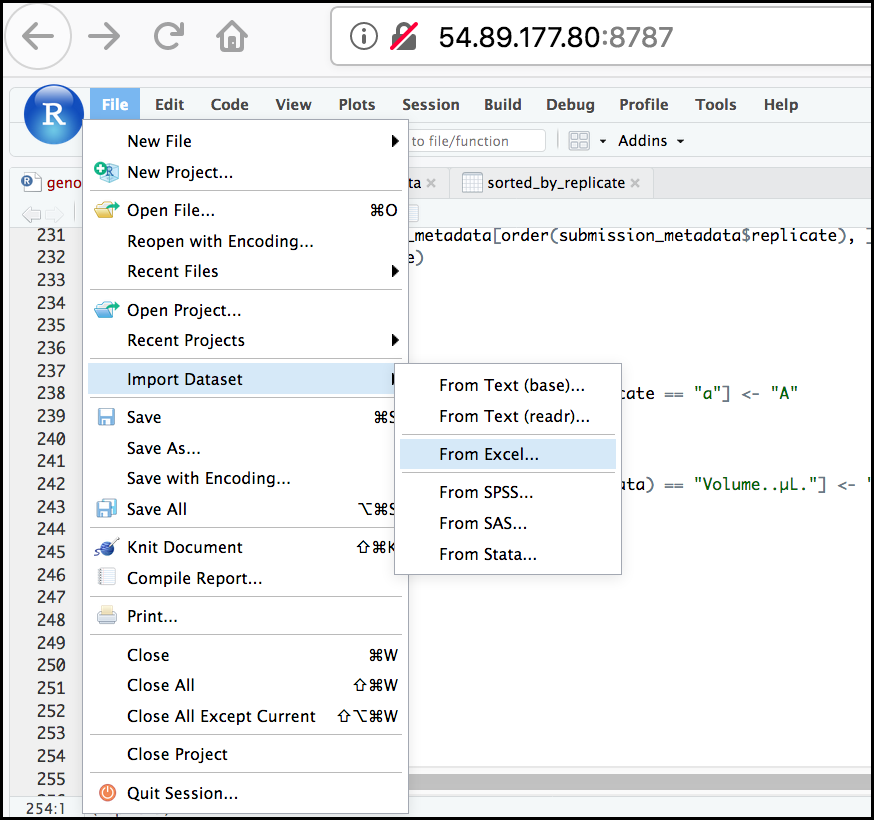

Importing data from Excel

Excel is one of the most common formats, so we need to discuss how to make these files play nicely with R. The simplest way to import data from Excel is to save your Excel file in .csv format*. You can then import into R right away. Sometimes you may not be able to do this (imagine you have data in 300 Excel files, are you going to open and export all of them?).

One common R package (a set of code with features you can download and add to your R installation) is the readxl package which can open and import Excel files. Rather than addressing package installation this second (we’ll discuss this soon!), we can take advantage of RStudio’s import feature which integrates this package. (Note: this feature is available only in the latest versions of RStudio such as is installed on our cloud instance).

First, in the RStudio menu go to File, select Import Dataset, and choose From Excel… (notice there are several other options you can explore).

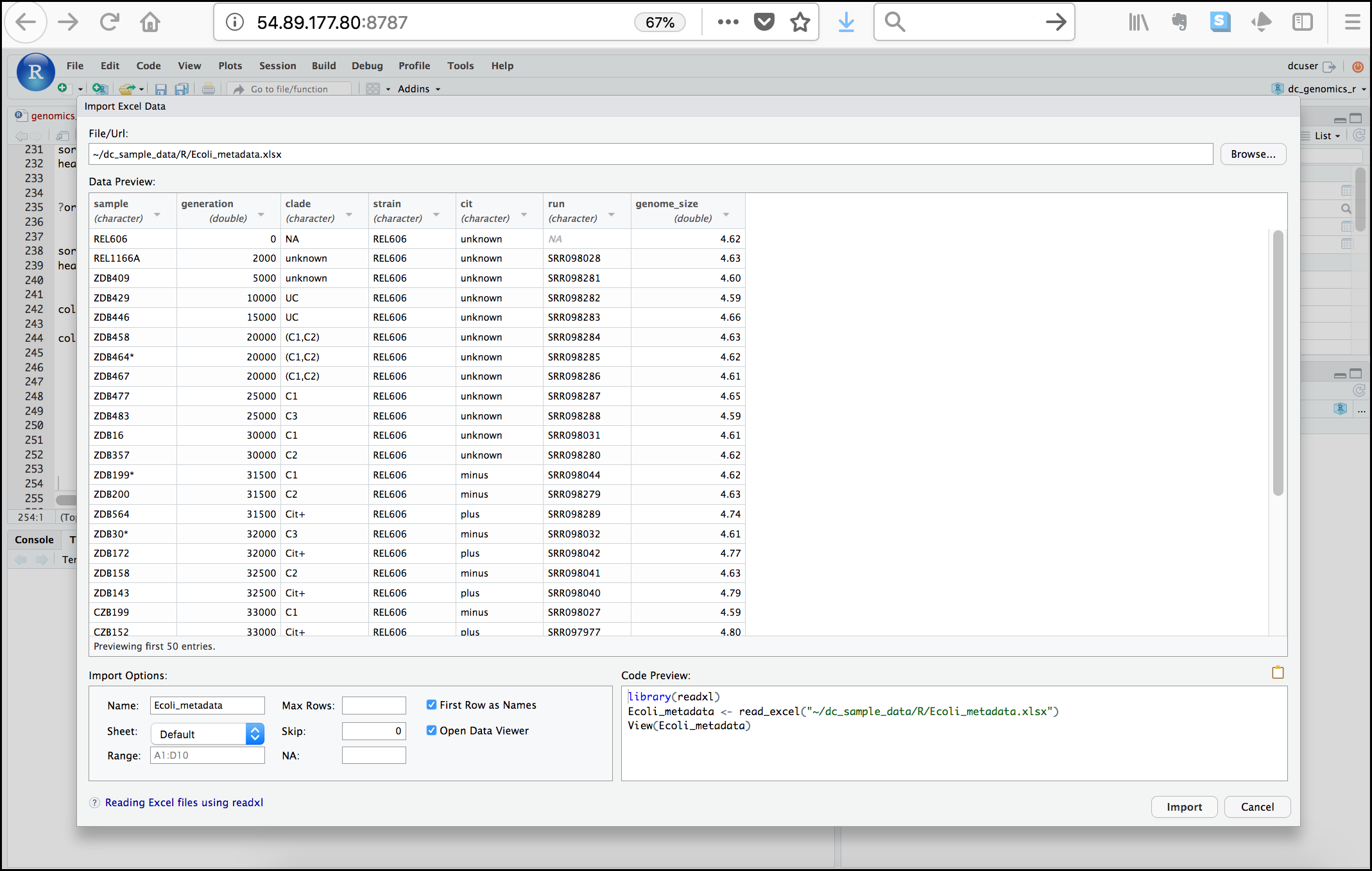

Next, under File/Url: click the Browse

button and navigate to the Ecoli_metadata.xlsx file

located at /home/dcuser/dc_sample_data/R. You should now

see a preview of the data to be imported:

Notice that you have the option to change the data type of each variable by clicking arrow (drop-down menu) next to each column title. Under Import Options you may also rename the data, choose a different sheet to import, and choose how you will handle headers and skipped rows. Under Code Preview you can see the code that will be used to import this file. We could have written this code and imported the Excel file without the RStudio import function, but now you can choose your preference.

In this exercise, we will leave the title of the data frame as Ecoli_metadata, and there are no other options we need to adjust. Click the Import button to import the data.

Finally, let’s check the first few lines of the

Ecoli_metadata data frame:

R

head(Ecoli_metadata)

OUTPUT

# A tibble: 6 × 7

sample generation clade strain cit run genome_size

<chr> <dbl> <chr> <chr> <chr> <chr> <dbl>

1 REL606 0 NA REL606 unknown <NA> 4.62

2 REL1166A 2000 unknown REL606 unknown SRR098028 4.63

3 ZDB409 5000 unknown REL606 unknown SRR098281 4.6

4 ZDB429 10000 UC REL606 unknown SRR098282 4.59

5 ZDB446 15000 UC REL606 unknown SRR098283 4.66

6 ZDB458 20000 (C1,C2) REL606 unknown SRR098284 4.63The type of this object is ‘tibble’, a type of data frame we will

talk more about in the ‘dplyr’ section. If you needed a true R data

frame you could coerce with as.data.frame().

Exercise: Putting it all together - data frames

Using the Ecoli_metadata data frame created

above, answer the following questions

What are the dimensions (# rows, # columns) of the data frame?

What are categories are there in the

citcolumn? hint: treat column as factorHow many of each of the

citcategories are there?What is the genome size for the 7th observation in this data set?

What is the median value of the variable

genome_sizeRename the column

sampletosample_idCreate a new column (name genome_size_bp) and set it equal to the genome_size multiplied by 1,000,000

Save the edited Ecoli_metadata data frame as “exercise_solution.csv” in your current working directory.

R

dim(Ecoli_metadata)

OUTPUT

[1] 30 7R

levels(as.factor(Ecoli_metadata$cit))

OUTPUT

[1] "minus" "plus" "unknown"R

table(as.factor(Ecoli_metadata$cit))

OUTPUT

minus plus unknown

9 9 12 R

Ecoli_metadata[7, 7]

OUTPUT

# A tibble: 1 × 1

genome_size

<dbl>

1 4.62R

median(Ecoli_metadata$genome_size)

OUTPUT

[1] 4.625R

colnames(Ecoli_metadata)[colnames(Ecoli_metadata) == "sample"] <- "sample_id"

Ecoli_metadata$genome_size_bp <- Ecoli_metadata$genome_size * 1000000

write.csv(Ecoli_metadata, file = "exercise_solution.csv")

- It is easy to import data into R from tabular formats including Excel. However, you still need to check that R has imported and interpreted your data correctly

- There are best practices for organizing your data (keeping it tidy) and R is great for this

- Base R has many useful functions for manipulating your data, but all of R’s capabilities are greatly enhanced by software packages developed by the community