Python basics

Last updated on 2023-05-04 | Edit this page

Estimated time: 55 minutes

Overview

Questions

- How do I assign values to variables?

- How do I do arithmetic?

- What is a built-in function?

- How do I see results?

- What data types are supported in Python?

Objectives

- Create different cell types and show/hide output in Jupyter

- Create variables and assign values to them

- Check the type of a variable

- Perform simple arithmetic operations

- Specify parameters when using built-in functions

- Get help for built-in functions and other aspects of Python

- Define native data types in Python

- Convert from one data type to another

Using the Jupyter environment

New cells

From the insert menu item you can insert a new cell anywhere in the

notebook either above or below the current cell. You can also use the

+ button on the toolbar to insert a new cell below.

Change cell type

By default new cells are created as code cells. From the cell menu item you can change the type of a cell from code to Markdown. Markdown is a markup language for formatting text, it has much of the power of HTML, but is specifically designed to be human-readable as well. You can use Markdown cells to insert formatted textual explanation and analysis into your notebook. For more information about Markdown, check out these resources:

Hiding output

When you run cells of code the output is displayed immediately below the cell. In general this is convenient. The output is associated with the cell that produced it and remains a part of the notebook. So if you copy or move the notebook the output stays with the code.

However lots of output can make the notebook look cluttered and more

difficult to move around. So there is an option available from the

cell menu item to ‘toggle’ or ‘clear’ the output associated

either with an individual cell or all cells in the notebook.

Creating variables and assigning values

Variables and Types

In Python variables are created when you first assign values to them.

All variables have a data type associated with them. The data type is

an indication of the type of data contained in a variable. If you want

to know the type of a variable you can use the built-in

type() function.

OUTPUT

<class 'int'>

<class 'float'>

<class 'str'>There are many more data types available, a full list is available in the Python documentation. We will be looking a few of them later on.

Arithmetic operations

For now we will stick with the numeric types and do some arithmetic.

All of the usual arithmetic operators are available.

In the examples below we also introduce the Python comment symbol

#. Anything to the right of the # symbol is

treated as a comment. To a large extent using Markdown cells in a

notebook reduces the need for comments in the code in a notebook, but

occasionally they can be useful.

We also make use of the built-in print() function, which

displays formatted text.

PYTHON

print("a =", a, "and b =" , b)

print(a + b) # addition

print(a * b) # multiplication

print(a - b) # subtraction

print(a / b) # division

print(b ** a) # exponentiation

print(a % b) # modulus - returns the remainder

print(2 * a % b) # modulus - returns the remainderOUTPUT

a = 2 and b = 3.142

5.1419999999999995

6.284

-1.142

0.6365372374283896

9.872164

2.0

0.8580000000000001We need to use the print() function because by default

only the last output from a cell is displayed in the output cell.

In our example above, we pass four different parameters to the first

call of print(), each separated by a comma. A string

"a = ", followed by the variable a, followed

by the string "b = " and then the variable

b.

The output is what you would probably have guessed at.

All of the other calls to print() are only passed a

single parameter. Although it may look like 2 or 3, the expressions are

evaluated first and it is only the single result which is seen as the

parameter value and printed.

In the last expression a is multiplied by 2 and then the

modulus of the result is taken. Had we wanted to calculate a % b and

then multiply the result by two we could have done so by using brackets

to make the order of calculation clear.

When we have more complex arithmetic expressions, we can use parentheses to be explicit about the order of evaluation:

PYTHON

print("a =", a, "and b =" , b)

print(a + 2*b) # add a to two times b

print(a + (2*b)) # same thing but explicit about order of evaluation

print((a + b)*2) # add a and b and then multiply by twoOUTPUT

a = 2 and b = 3.142

8.283999999999999

8.283999999999999

10.283999999999999Arithmetic expressions can be arbitrarily complex, but remember people have to read and understand them as well.

Exercise

Create a new cell and paste into it the assignments to the variables a and b and the contents of the code cell above with all of the print statements. Remove all of the calls to the print function so you only have the expressions that were to be printed and run the code. What is returned?

Now remove all but the first line (with the 4 items in it) and run the cell again. How does this output differ from when we used the print function?

Practice assigning values to variables using as many different operators as you can think of.

Create some expressions to be evaluated using parentheses to enforce the order of mathematical operations that you require

- Only the last result is printed.

- The 4 ‘items’ are printed by the REPL, but not in the same way as

the print statement. The items in quotes are treated as separate

strings, for the variables a and b the values are printed. All four

items are treated as a ‘tuple’ which are shown in parentheses, a tuple

is another data type in Python that allows you to group things together

and treat as a unit. We can tell that it is a tuple because of the

()

A complete set of Python operators can be found in the official documentation . The documentation may appear a bit confusing as it initially talks about operators as functions whereas we generally use them as ‘in place’ operators. Section 10.3.1 provides a table which list all of the available operators, not all of which are relevant to basic arithmetic.

Using built-in functions

Python has a reasonable number of built-in functions. You can find a complete list in the official documentation.

Additional functions are provided by 3rd party packages which we will look at later on.

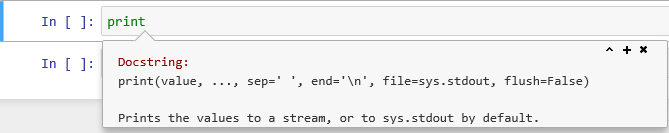

For any function, a common question to ask is: What parameters does this function take?

In order to answer this from Jupyter, you can type the function name

and then type shift+tab and a pop-up window

will provide you with various details about the function including the

parameters.

Exercise

For the print() function find out what parameters can be

provided

Type ‘print’ into a code cell and then type

shift+tab. The following pop-up should

appear.

Getting Help for Python

You can get help on any Python function by using the help function. It takes a single parameter of the function name for which you want the help.

OUTPUT

Help on built-in function print in module builtins:

print(...)

print(value, ..., sep=' ', end='\n', file=sys.stdout, flush=False)

Prints the values to a stream, or to sys.stdout by default.

Optional keyword arguments:

file: a file-like object (stream); defaults to the current sys.stdout.

sep: string inserted between values, default a space.

end: string appended after the last value, default a newline.

flush: whether to forcibly flush the stream.There is a great deal of Python help and information as well as code examples available from the internet. One popular site is stackoverflow which specialises in providing programming help. They have dedicated forums not only for Python but also for many of the popular 3rd party Python packages. They also always provide code examples to illustrate answers to questions.

You can also get answers to your queries by simply inputting your question (or selected keywords) into any search engine.

A couple of things you may need to be wary of: There are currently 2 versions of Python in use, in most cases code examples will run in either but there are some exceptions. Secondly, some replies may assume a knowledge of Python beyond your own, making the answers difficult to follow. But for any given question there will be a whole range of suggested solutions so you can always move on to the next.

Data types and how Python uses them

Changing data types

The data type of a variable is assigned when you give a variable a value as we did above. If you re-assign the value of a variable, you can change the data type.

You can also explicitly change the type of a variable by

casting it using an appropriate Python builtin function. In

this example we have changed a string to a

float.

OUTPUT

<class 'str'>

<class 'float'>Although you can always change an integer to a

float, if you change a float to an

integer then you can lose part of the value of the variable

and you won’t get an error message.

PYTHON

a = 3.142

print(type(a))

a = 3

print(type(a))

a = a*1.0

print(type(a))

a = int(a)

print(type(a))

a = 3.142

a = int(a)

print(type(a))

print(a)OUTPUT

<class 'float'>

<class 'int'>

<class 'float'>

<class 'int'>

<class 'int'>

3In some circumstances explicitly converting a data type makes no sense; you cannot change a string with alphabetic characters into a number.

OUTPUT

<class 'str'>

---------------------------------------------------------------------------

ValueError Traceback (most recent call last)

<ipython-input-8-9f5f81a470f9> in <module>()

2 print(type(b))

3

----> 4 b = int(b)

5 print(type(b))

ValueError: invalid literal for int() with base 10: 'Hello World'Strings

A string is a simple data type which holds a sequence of characters.

Strings are placed in quotes when they are being assigned, but the quotes don’t count as part of the string value.

If you need to use quotes as part of your string you can arbitrarily use either single or double quotes to indicate the start and end of the string.

PYTHON

mystring = "Hello World"

print(mystring)

name = "Peter"

mystring = 'Hello ' + name + ' How are you?'

print(mystring)

name = "Peter"

mystring = 'Hello this is ' + name + "'s code"

print(mystring)OUTPUT

Hello World

Hello Peter How are you?

Hello this is Peter's codeString functions

There are a variety of Python functions available for use with

strings. In Python a string is an object. An object put simply is

something which has data, in the case of our string it is

the contents of the string and methods.

methods is another way of saying

functions.

Although methods and functions are very

similar in practice, there is a difference in the way you call them.

One typical bit of information you might want to know about a string

is its length for this we use the len() function. For

almost anything else you might want to do with strings, there is a

method.

OUTPUT

11The official documentation says, ‘A method is a function that “belongs to” an object. In Python, the term method is not unique to class instances: other object types can have methods as well. For example, list objects have methods called append, insert, remove, sort, and so on.’.

If you want to see a list of all of the available methods for a

string (or any other object) you can use the dir()

function.

OUTPUT

['__add__', '__class__', '__contains__', '__delattr__', '__dir__', '__doc__', '__eq__', '__format__', '__ge__', '__getattribute__', '__getitem__', '__getnewargs__', '__gt__', '__hash__', '__init__', '__iter__', '__le__', '__len__', '__lt__', '__mod__', '__mul__', '__ne__', '__new__', '__reduce__', '__reduce_ex__', '__repr__', '__rmod__', '__rmul__', '__setattr__', '__sizeof__', '__str__', '__subclasshook__', 'capitalize', 'casefold', 'center', 'count', 'encode', 'endswith', 'expandtabs', 'find', 'format', 'format_map', 'index', 'isalnum', 'isalpha', 'isdecimal', 'isdigit', 'isidentifier', 'islower', 'isnumeric', 'isprintable', 'isspace', 'istitle', 'isupper', 'join', 'ljust', 'lower', 'lstrip', 'maketrans', 'partition', 'replace', 'rfind', 'rindex', 'rjust', 'rpartition', 'rsplit', 'rstrip', 'split', 'splitlines', 'startswith', 'strip', 'swapcase', 'title', 'translate', 'upper', 'zfill']The methods starting with __ are special or magic

methods which are not normally used.

Some examples of the methods are given below. We will use others when we start reading files.

PYTHON

myString = "The quick brown fox"

print(myString.startswith("The"))

print(myString.find("The")) # notice that string positions start with 0 like all indexing in Python

print(myString.upper()) # The contents of myString is not changed, if you wanted an uppercase version

print(myString) # you would have to assign it to a new variableOUTPUT

True

0

THE QUICK BROWN FOX

The quick brown foxThe methods starting with ‘is…’ return a boolean value of either True or False

OUTPUT

Falsethe example above returns False because the space character is not considered to be an Alphanumeric value.

In the example below, we can use the replace() method to

remove the spaces and then check to see if the result

isalpha chaining method in this way is quite common. The

actions take place in a left to right manner. You can always avoid using

chaining by using intermediary variables.

OUTPUT

TrueFor example, the following is equivalent to the above

OUTPUT

TrueIf you need to refer to a specific element (character) in a string,

you can do so by specifying the index of the character in

[] you can also use indexing to select a substring of the

string. In Python, indexes begin with 0 (for a visual,

please see Strings

and Character Data in Python: String Indexing or 9.4.

Index Operator: Working with the Characters of a String).

PYTHON

myString = "The quick brown fox"

print(myString[0])

print(myString[12])

print(myString[18])

print(myString[0:3])

print(myString[0:]) # from index 0 to the end

print(myString[:9]) # from the beginning to one before index 9

print(myString[4:9])OUTPUT

T

o

x

The

The quick brown fox

The quick

quickBasic Python data types

So far we have seen three basic Python data types; Integer, Float and

String. There is another basic data type; Boolean. Boolean variables can

only have the values of either True or False.

(Remember, Python is case-sensitive, so be careful of your spelling.) We

can define variables to be of type boolean by setting their value

accordingly. Boolean variables are a good way of coding anything that

has a binary range (eg: yes/no), because it’s a type that computers know

how to work with as we will see soon.

PYTHON

print(True)

print(False)

bool_val_t = True

print(type(bool_val_t))

print(bool_val_t)

bool_val_f = False

print(type(bool_val_f))

print(bool_val_f)OUTPUT

True

False

<class 'bool'>

True

<class 'bool'>

FalseFollowing two lines of code will generate error because Python is case-sensitive. We need to use ‘True’ instead of ‘true’ and ‘False’ instead of ‘false’.

OUTPUT

NameError Traceback (most recent call last)

<ipython-input-115-b5911eeae48b> in <module>

----> 1 print(true)

2 print(false)

NameError: name 'true' is not definedWe can also get values of Boolean type using comparison operators,

basic ones in Python are == for “equal to”, !=

for “not equal to”, and >, <, or

>=, <=.

PYTHON

print('hello' == 'HELLO')

print('hello' is 'hello')

print(3 != 77)

print(1 < 2)

print('four' > 'three')OUTPUT

False

True

True

True

FalseExercise

Imagine you are considering different ways of representing a boolean

value in your data set and you need to see how python will behave based

on the different choices. Fill in the blanks using the built in

functions we’ve seen so far in following code excerpt to test how Python

interprets text. Write some notes for your research team on how to code

True and False as they record the

variable.

PYTHON

bool_val1 = 'TRUE'

print('read as type ',___(bool_val1))

print('value when cast to bool',___(bool_val1))

bool_val2 = 'FALSE'

print('read as type ',___(bool_val2))

print('value when cast to bool',___(bool_val2))

bool_val3 = 1

print('read as type ',___(bool_val3))

print('value when cast to bool',___(bool_val3))

bool_val4 = 0

print('read as type ',___(bool_val4))

print('value when cast to bool',___(bool_val4))

bool_val5 = -1

print('read as type ',___(bool_val5))

print('value when cast to bool',___(bool_val5))

print(bool(bool_val5))0 is represented as False and everything else, whether a number or string is counted as True

Structured data types

A structured data type is a data type which is made up of some combination of the base data types in a well defined but potentially arbitrarily complex way.

The list

A list is a set of values, of any type separated by commas and delimited by ‘[’ and ’]’

PYTHON

list1 = [6, 54, 89 ]

print(list1)

print(type(list1))

list2 = [3.142, 2.71828, 9.8 ]

print(list2)

print(type(list2))

myname = "Peter"

list3 = ["Hello", 'to', myname ]

print(list3)

myname = "Fred"

print(list3)

print(type(list3))

list4 = [6, 5.4, "numbers", True ]

print(list4)

print(type(list4))OUTPUT

[6, 54, 89]

<class 'list'>

[3.142, 2.71828, 9.8]

<class 'list'>

['Hello', 'to', 'Peter']

['Hello', 'to', 'Peter']

<class 'list'>

[6, 5.4, 'numbers', True]

<class 'list'>Exercise

We can index lists the same way we indexed strings before. Complete

the code below and display the value of last_num_in_list

which is 11 and values of odd_from_list which are 5 and 11

to check your work.

PYTHON

# Solution 1: Basic ways of solving this exercise using the core Python language

num_list = [4,5,6,11]

last_num_in_list = num_list[-1]

print(last_num_in_list)

odd_from_list = [num_list[1], num_list[3]]

print(odd_from_list)

# Solutions 2 and 3: Usually there are multiple ways of doing the same work. Once we learn about more advanced Python, we would be able to write more varieties codes like the followings to print the odd numbers:

import numpy as np

num_list = [4,5,6,11]

# Converting `num_list` list to an advanced data structure: `numpy array`

num_list_np_array = np.array(num_list)

# Filtering the elements which produces a remainder of `1`, after dividing by `2`

odd_from_list = num_list_np_array[num_list_np_array%2 == 1]

print(odd_from_list)

# or, Using a concept called `masking`

# Create a boolean list `is_odd` of the same length of `num_list` with `True` at the position of the odd values.

is_odd = [False, True, False, True] # Mask array

odd_from_list = num_list_np_array[is_odd] # only the values at the position of `True` remain

print(odd_from_list)The range function

In addition to explicitly creating lists as we have above it is very

common to create and populate them automatically using the

range() function in combination with the

list() function

OUTPUT

[0, 1, 2, 3, 4]Unless told not to range() returns a sequence which

starts at 0, counts up by 1 and ends 1 before the value of the provided

parameter.

This can be a cause of confusion. range(5) above does

indeed have 5 values, but rather than being 1,2,3,4,5 which you might

naturally think, they are in fact 0,1,2,3,4. The range starts at 0 and

stops one before the value of the single parameter we specified.

If you want different sequences, then you can modify the behavior of

the range() function by using additional parameters.

OUTPUT

[1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8]

[2, 4, 6, 8, 10]When you specify 3 parameters as we have for list(7); the first is start value, the second is one past the last value and the 3rd parameter is a step value by which to count. The step value can be negative

list7 produces the even numbers from 1 to 10.

Exercise

- What is produced if you change the step value in

list7to -2 ? Is this what you expected? - Create a list using the

range()function which contains the even number between 1 and 10 in reverse order ([10,8,6,4,2])

The other main structured data type is the Dictionary. We will introduce this in a later episode when we look at JSON.

- The Jupyter environment can be used to write code segments and display results

- Data types in Python are implicit based on variable values

- Basic data types are Integer, Float, String and Boolean

- Lists and Dictionaries are structured data types

- Arithmetic uses standard arithmetic operators, precedence can be changed using brackets

- Help is available for builtin functions using the

help()function further help and code examples are available online - In Jupyter you can get help on function parameters using shift+tab

- Many functions are in fact methods associated with specific object types